Proponents of classical dressage principles have long believed that horses trained with these methods stay sounder in mind and body and enjoy longer careers than those trained using short cuts, gadgets, or other fly-by-night methods. Recent research, in particular work by Dr. Hilary Clayton in North America and Dr. Gerd Heuschmann in Europe, has now provided empirical evidence that classical techniques are both horse-friendly and biomechanically correct.

But what some dressage lovers might not realize is that the term “classical dressage techniques” is itself somewhat of a misnomer. Rather than existing somewhere as a list of specific rules or rigid instructions that must be followed (a lá the Ten Commandments), the development of classical dressage principles has evolved alongside the horse himself. In the millennia since humans first domesticated the equine species, the type and style of preferred horse, tack, and manner of use has changed significantly. With increasing sophistication in our expectations of the horse came an evolution in understanding how best to train them.

Unfortunately, in some parts of the world, many written works and other documentation of training practices have been lost to time, and we may never know the specific contributions that some horsemen (particularly from non-European cultures) may have made to dressage training. However, other texts have been preserved, and many of these still provide guidance and training tips for the modern rider.

Shop the Blog

Xenophon

In 350 BCE, the Greek historian and soldier Xenophon wrote his treatise, “On Horsemanship,” which many equestrian scholars believe to be one of the earliest texts on the subject. Xenophon advocates for the development of a supple, balanced seat in the rider and touches on concepts that we might call “feel” today. Xenophon also describes the use of transitions, circles, and work on hills. Athenian horses were not ridden in saddles, and perhaps this is the reason why Xenophon describes little to no work in the trot, which of course is the bounciest gait!

Scholars believe that the horses of Athens in Xenophon’s time were hot-blooded and required tactful riding, which is perhaps why he also encouraged riders to treat the horses with compassion. While Xenophon’s work does discuss cross-country riding (which made horses bolder for hunting or warfare) and the development of the “high school movements” (giving nobility a “proud appearance during parades”), he does not cover the development of young horses. This is possibly because the book was intended for the use of nobility, who only rode trained animals.

Though Xenophon’s work seemingly did not influence the way Romans handled horses during their period of dominance, it resurfaced several hundred years later during the Renaissance and is credited for inspiring many horsemen of that era.

During the Renaissance, many noblemen and royals became patrons of the equestrian arts, founding riding schools and supporting the training of horses for use in parades and equestrian pageants. Xenophon’s work was rediscovered by Roman expatriates, and his techniques were combined with the use of saddles and leverage bits. With the development of firearms came a reduced need for powerful mounts to carry heavy knights, and horses were bred to be lighter and more agile. The Spanish Riding School of Vienna, Austria, was founded in 1572 during the Hapsburg Monarchy, and is the oldest surviving school of this era.

Federico Grisone

The Neapolitan nobleman Federico Grisone is often credited with establishing the first riding school teaching dressage in the early 1500s. Most of Grisone’s horses were schoolmasters used to train young noblemen how to ride. Scholars of the time described Grisone’s methods as being highly influenced by the writings of Xenophon. However, Grisone used the trot to increase the horse’s suppleness a emphasized the importance of securing the position of the horse’s neck starting at its base, concepts not discussed in Xenophon’s work.

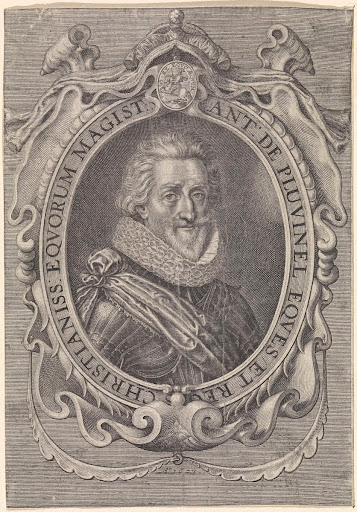

Antoine de Pluvinel

A popular quote attributed to Pluvinel is as follows:

“You can never rely on a horse educated by fear; there is always something he fears more than you. But, when he trusts you, he will do what you ask when he is afraid.”

William Cavendish (Duke of Newcastle)

The British Duke of Newcastle, William Cavendish, established a riding school at Bolsover Castle in 1634, and in 1658 published “A General System of Horsemanship.”

A former military officer, Cavendish recognized the need for more agility in cavalry mounts, and he is credited with introducing the turn on the forehand (sideways volte) as a suppling exercise. Cavendish’s sympathetic approach to horse training included teaching them to seek and accept the outside aids, to yield to a unilateral inside aid, and to bring the horse’s hind legs close together for true collection. Cavendish primarily used snaffle bits and cavesson nosebands. His schooling arena was similar in design to the arenas of today.

Francois Robichon de la Guérinière

For many equestrian scholars, Francois Robichon de la Guérinière (1688-1751) was perhaps the most influential French master, establishing many concepts still practiced in classical training programs today. De la Guérinière believed that the basic training of the young horse should be the same, regardless of his future career; he developed the use of the counter canter for straightening and strengthening the horse, promoted the use of shoulder-in, and emphasized the use of the trot for most fundamental dressage work. De la Guérinière began work in a snaffle and progressed to either a double bit or a pelham with two reins. In training the rider, de la Guérinière believed that only precise coordination of the aids would allow for the proper execution of movements such as piaffe, passage, and the airs above the ground.

In the late 1700s, the French Revolution devastated the continued development of equestrian art in that country for a time, but progress continued in other areas, particularly Germany. In 1817, a German organization was founded in Berlin to “teach the training of horse and rider according to uniform principles.” First based at the Cavalry School at Schwedt (Oder) and then moved to Hanover beginning in 1867, these German schools spread the teaching of “classical riding.”

Gustav Steinbrecht

Gustav Steinbrecht is perhaps best known for his work, “Gymnasium of the Horse,” a guideline for classical riding published in 1885. This work would later become the foundation for training manuals used by both the U.S and German Dressage Federations. Steinbrecht was originally interested in training horses for the circus using classical principles. Circuses were quite popular at the time, but many masters felt they exposed audiences to a simplified version of dressage and were harmful to classical training practices. In his work, Steinbrecht highlights the importance of developing rhythmical paces in the horse, and enhancing swing in the topline and straight movement, while maintaining relaxation and an even acceptance of the bit. The motto “ride your horse forward and straighten him” is attributed to Steinbrecht.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, cavalry schools dominated the teaching of equitation skills. Officers were frequently exchanged among different programs, allowing for the spread and integration of new ideas. Some of the most dominant schools were at Hanover (Germany), Pinerolo and Tor di Quinto (Italy), the Spanish Riding School (Austria), and the French Training Center at Saumur. After World War I, training methods espoused by these schools were a blend of older classical techniques and the more modern “forward” approaches favored by the cavalry. With the evolution of modern military techniques during World War II, cavalries fell to the wayside and many former officers began teaching classical horsemanship to civilians.

While some argue that classical and competitive dressage are two distinct branches of the same tree, there are many trainers and riders who seek to maintain the use of classical, progressive principles in modern sport. Today, enthusiasts can take inspiration from classical schools such as those at the Royal Andalusian School in Jerez, Spain, the Cadre Noir in Saumur, France, the Portuguese School of Equestrian Art in Sintra, Portugal, and of course, the Spanish Riding School in Vienna, Austria, as well as the works of the great masters.

Walter Zettl

Walter Zettl, born in Altrohlau, Czechoslovakia in 1929, was an accomplished horseman who received his equestrian education in Germany at a time when the traditional cavalry methods of horse training were still merging with art and modern sport. He dedicated his career to teaching not only the correct theoretical basis to his training system, but also promoting the development of a harmonious and sympathetic relationship between horse and rider.

In 2002, Premier Equestrian founders Mark Neihart and Heidi Zorn began documenting clinics and video interviews with the great classical dressage master to create a five-volume series, “A Matter of Trust,”. Zettl passed away in 2018, but his teaching of classical horsemanship theory lives on.

“A Matter of Trust, Volume I” is now available on YouTube for free access.

Shop the Blog

-

Sale!

Modern Colonial Dressage Flower Boxes

Price range: $1,027.76 through $2,036.6618″ or 22″ Tall, Set of 8 or 12

Free Shipping in the contiguous U.S.

-

Sale!

Modern Colonial Flower Boxes

Price range: $107.10 through $152.1018″ or 22″ Tall

Free Shipping in the contiguous U.S.

-

Sale!

Sundance Arena Short Rail

Price range: $3,325.50 through $3,955.5020×60 and 20×40 meters

9′ 3.5″ long rails

Free Shipping in the contiguous U.S.

-

Sale!

Sundance Arena Upgrade to 20×60

Price range: $1,327.50 through $2,515.50For 20×40 meter and Training Sets

Free Shipping in the contiguous U.S.

-

Sale!

Sundance Arena Rails – 10 Pack

Original price was: $1,395.00.$1,255.50Current price is: $1,255.50.Free Shipping in the contiguous U.S.

-

Sale!

Sundance Dressage Training Arena

Price range: $1,665.00 through $2,425.5020×60 meters with open sections

Free Shipping in the contiguous U.S.

-

Sale!

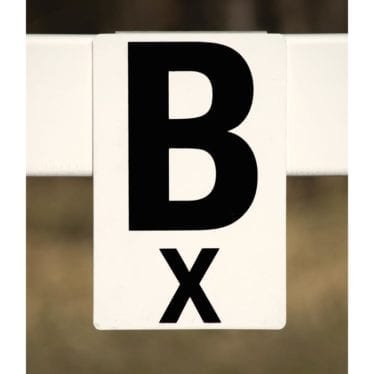

Tower Dressage Arena Letters

Price range: $1,032.26 through $1,525.50Sets of 12 or 8

Free Shipping in the contiguous U.S.

-

Sale!

Wall Dressage Arena Letters

Price range: $170.96 through $211.46Sets of 12 or 8

Free Shipping in the contiguous U.S.

-

Sale!

Dressage Arena Rail Letters

Price range: $179.96 through $251.96Sets of 12 or 8

Free Shipping in the contiguous U.S.

-

Sale!

Elite Dressage Arena Letters

Price range: $294.26 through $746.96Sets of 12 or 8

Free Shipping in the contiguous U.S.

-

Sale!

Berkshire Dressage Arena Letters

Price range: $742.50 through $985.50Sets of 8 or 12

Free Shipping in the contiguous U.S.

-

Sale!

Wellington Arena with Tower Letters Package

Price range: $4,182.66 through $5,230.04

About the author

Christina Keim is a professional equestrian and writer based at Cold Moon Farm in Rochester, NH. Over the course of her career, she has worked as a barn manager, head groom, riding instructor, and collegiate equestrian team coach. In 2015, she founded Cold Moon Farm with the mission to promote sustainable living, conservation, and the highest standards of compassionate horsemanship.